So far, this country has been the biggest loser from President Trump’s tariffs

The Trump Administration brought a bit more clarity to the Section 232 “national security” tariffs being imposed on steel (25%) and aluminum (10%). Korea and the US have meanwhile settled their differences, and the US and China are in negotiations. But there’s still lack of clarity as to how countries will be exempted from US tariffs and what products will be excluded. More importantly, basic economics tells us that the Trump tariffs won’t affect the US trade balance in the least.

The following is the updated weekly report of our trade correspondent, L.C.

Country exemptions

In a March 22nd proclamation, President Trump said tariffs on seven countries (the EU, Canada, Mexico, Australia, South Korea, Argentina, and Brazil) would be delayed until May 1st, but then the tariffs would apply unless “I determine by further proclamation that the US has reached a satisfactory alternative means” to address “threatened impairment” of the steel [or aluminum] sector.”

The brief postponement of tariffs likely delayed the planned retaliation and World Trade Organization (WTO) complaints that trading partners such as the European Union (EU) had been prepared to take. But since China was not exempted, it announced its own planned retaliation.

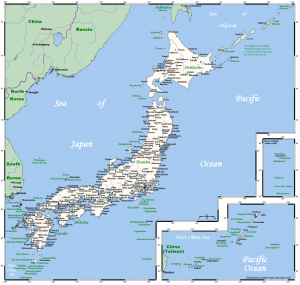

Regarding country exemptions, for which US Trade Representative (USTR) Lighthizer is responsible, the most startling development this week was the announcement that Japan was not granted the temporary exemption granted to the seven other major metals suppliers.

Japanese officials presented their case for exemption to US officials, and Japan’s case would seem to have been stronger than Brazil’s and Argentina’s, given strong US-Japanese military ties. Indeed, under Prime Minister Abe’s leadership, Japan has become the de facto leader of the free world in the Pacific since President Trump withdrew the US from the Trans-Pacific Alliance (TPA). Not wishing to turn the Pacific over to Chinese domination, Prime Minister Abe revived the TPA minus the US. Moreover, Japanese steel is complementary rather than competitive with US steel and will be difficult for US manufacturers to replace.

While it is not clear what the US wants from Japan. most likely it is agreement its to a Voluntary Export Restraint on steel and/or aluminum exports to the US. In fact, the US wants all countries, whether subjected to tariffs or not, to voluntarily impose on themselves export quotas to the US. Trump trade adviser Peter Navarro said this directly to reporters: “For all countries, there has to be a quota.” If any country doesn’t have a quota, he said, it could become a transshipment point other countries could use to sneak their products into the US.

But such Voluntary Restraint Agreements are illegal in the World Trade Organizations (WTO).

Product exclusions

The process for US companies to obtain product exclusions for imports they need will be at least as burdensome as the temporary country exemptions. US companies seeking a specific product excluded from the tariffs must apply to the Commerce Department’s Bureau of Industry & Security (BIS). The details of the process were released this past week and suggest that relief will be difficult to get, time-consuming, and costly.

China?

Chinese Vice-President Wang Qishan, China’s chief trade negotiator with the US

Most US politicians, businesses, and foreign governments think the target of US action should be narrowly focused on China and its subsidized overcapacity. Commerce Secretary Ross told the House Ways & Means that he expects the tariffs to spur a multilateral effort against China’s overcapacity in metals.

China found itself targeted by the US twice this week. First, China was targeted when it was not among the countries granted temporary exemptions from the Section 232 tariffs. Then it was targeted when the President announced on March 22nd that he had directed US Trade Representative (USTR) Lighthizer to develop a plan to penalize China through tariffs and other means under Section 301. That section of US trade law authorizes retaliation against a government that discriminates against U.S. commerce.

China responded by announcing its own tariff plan to retaliate against the threatened steel and aluminum tariffs. The list included fruit, nuts, wine, ethanol, and seamless steel pipes (15% tariff) and pork and recycled aluminum (25% tariff). Some US farmers would be hard hit.

US and Chinese trade officials are now trying to settle their disagreements. The announcement over the weekend that negotiations are underway was a great relief to stock markets worldwide. On Monday, markets recovered from their trade-war-inspired swoon of the previous week.

What me worry about Economics 101?

But there’s one problem with all these loud promises by President Trump to reduce the US trade deficit: it won’t happen. An article in Monday’s Wall Street Journal explains why:

As recently as 2009, nearly half the U.S. trade deficit was driven by one product: petroleum. If ever a national strategy could be devised to tackle the trade gap by targeting an individual product or individual set of countries, American dependence on foreign oil was on its face the place to look.

The U.S. did, in fact, conquer its oil deficit and a trade deficit with the oil-producing nations of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries.

Instead of getting smaller, however, the U.S. trade gap widened.

The oil experience is evidence that you can’t shrink a national trade deficit by targeting one product or one country or set of countries. It also provides clues about what might happen next as the Trump administration tries to close the U.S. deficit with tariffs on steel, aluminum and a range of goods from China….

“The trade deficit doesn’t come from the fact that we’re importing this good or that good,” said James Hamilton, an economist at the University of California, San Diego, and a leading expert on the economics of oil. “The trade balance is primarily determined by the overall spending on goods and services by U.S. residents and firms, compared to production. If spending is more than production, we’ve got to import.”

… Trade balances writ large are a function of how much Americans invest and save. When domestic saving isn’t enough to cover investment, the balance is made up from abroad. Low saving leads to wider trade deficits. Conversely, high-saving countries, such as Germany and China, run surpluses that fund the consumption and investment of others.”

As economics texts note, one insight from the national saving and investment identity is that a nation’s balance of trade is determined by its level of domestic investment covered by domestic savings, taken together with its government expenses covered by taxes. The US is running a deficit in both its domestic (private sector) account and its government account. Those two deficits need to be financed by foreign dollars, which the lenders, the major exporting countries, acquire by sale of goods to the US. Hence the inevitability of the US trade deficit unless it drastically expands production, reduces the federal deficit, and increases private savings.

But finishing our wrap-up….

NAFTA

This week brought significant North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) developments, all pointing toward improved prospects for reaching a deal, even in the short term.

KORUS

Meanwhile, officials in Washington and Seoul say that a settlement has been reached in the US-South Korea FTA (KORUS) negotiations. But Forbes magazine is unimpressed.

G20

At the Group of 20 (G20) finance ministers’ and central bankers’ meeting in Buenos Aires on March 19th to 20th, the US once again blocked language from the final communiqué directly critical of protectionism. This was a replay of the role the US played last year at numerous major summit meetings. US Treasury Secretary Mnuchin reaffirmed President Trump’s tweet that the US isn’t afraid of a trade war – and the odd, bullying argument that the US would win because it is big and runs a trade deficit.

Mnuchin reiterated that the Section 232 tariffs were imposed to counter unfair trade practices, but this will make it that much harder to defend the tariffs at the WTO. If the tariffs aren’t for national security, they come under WTO rules which the US didn’t follow. Other countries can now challenge the US tariffs and receive compensation.

BREXIT

The European Council (EU leaders), meeting on March 23rd, approved guidelines for the transition period after the UK leaves the EU and for how the two sides will approach negotiations for the post-Brexit UK-EU trading relationship. The Ireland-Northern Ireland border status has not been settled yet, but it will be covered by an interim solution.

AfCFTA

Africa takes a big step toward creating a continental free trade area

At the March 21st African Union Summit in Kigali, the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) was launched, signed by 44 of the 55 members of the African Union. It is expected to encompass all Organization for African Unity member countries and about 1.2 billion people. Its objective is to form a continent-wide area with free flow of goods, people, and finances. But Nigeria, Africa’s largest economy, and ten other African countries have not yet signed the agreement.

Click here to go to the previous Founders Broadsheet post (“The revolution in climate science you probably haven’t heard”)

Leave a Reply