The centralized, monopolistic public school model isn’t serving the nation well any more

A new year is starting at schools and colleges around the US, but it’s business as usual in the education industry. Although the US has higher per pupil educational spending than anywhere else in the world, its students score a mediocre 28th place in global school rankings. China scores way ahead of the US in both science and math. These are the two subjects on which technological advances are based. This bodes ill for US economic well-being and military dominance.

This is a dangerous and unacceptable situation. The US is facing existential military threats from a hostile Russia and hostile China. Contrary to the American genius for innovation, we now have a largely monopolistic, over-regulated K-12 public school system and an expensive four-year college system that leaves many students heavily in debt, not all that wiser, and with diplomas that bear little correlation with the work they will be doing after graduation. This is occurring in the face of a severe labor shortage that could be alleviated if the estimated ninety percent of college attendees who aren’t really college material were working instead of pursuing degrees they don’t need.

So how do we address these two problems — of poor quality (by comparison with international competitors) and credentialism (the pursuit of unnecessary, time-wasting, debt-incurring diplomas)?

K-12

US kindergarten through twelfth grade (K-12) public schools are responsible for the education of 90% of the nation’s school age children. For that 90% not attending private academies, the public schools are highly regulated monopoly providers. Indeed, they are regulated simultaneously by four different bureaucracies — federal, state, local, and trade union — with the teachers colleges possibly qualifying as a fifth. Monopoly status combined with heavy regulation is a formula for stagnation and mediocrity in any domain. For this reason we believe that maximizing competition and minimizing regulation among K-12 school providers will greatly improve education quality. Competition would be maximized by each state if all parents were provided with vouchers so that they could send their children to schools of their choice or educate them at home. Schools could choose among competing independent testing companies for year-end assessments of student learning. Aggregate school scores would be published so that parents would have a basis for evaluating the comparative merits of the various local schools.

Why would states implement such a scheme in the face of extreme opposition from teachers unions and educational bureaucracies? First of all, universal vouchers already have strong public support. Secondly, they’ve been a success story elsewhere — for example, in Canada. Third, if, as we predict, states that implement such competition-enhancing schemes succeed in producing a better-educated work force at reasonable cost, those states will attract new industries and encourage the prosperity and enlargement of old ones. This will encourage other states to enact similar reforms.

These recommendations are hardly novel or radical. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos has a good discussion of reforms abroad that US school systems can emulate. Dissatisfaction with US education is long-standing and widespread. Johnny can read but not well and in too many cases won’t. He can’t write, and he is mediocre in math, science, history, economics, political science, and the humanities. Businesses are at wit’s end that Johnny doesn’t seem to have much to show for his high school diploma or four years of college. Experts throw up their hands at the middling performance of US students in international tests, despite higher per-pupil expenditures than anywhere else in the world. Multiple studies show that there is little correlation in the US between increased per pupil spending and increased academic achievement.

We don’t need the authoritarian national education systems that some high-ranking East Asian nations have adopted. What we do need to emulate is the high expectations that East Asian parents and schools convey as to what their children are capable of achieving.

Lowering of standards is pervasive

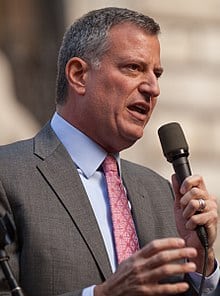

New York City mayor Bill de Blasio is a good example of why educational standards need protection through privatization

Instead, what do we see in some parts of the US? In New York City the mayor, Bill de Blasio, is leading a movement to lower the admission standards of the city’s elite public schools rather than working to raise academic standards at the non-elite schools. He is doing so as a sop to the city’s African-American population, disproportionately few of whose children can presently pass the elite schools’ entrance exams. This seeming interest of the mayor for the advancement of black students is easily exposed as a sham. If he really cared about minority education he would not have become the full-time enemy of the city’s high-achieving charter schools, which have proved far better at educating black and Hispanic students than the public schools.

Grade inflation. Throughout the nation, K-12 schools are inflating grades so that students can pass to the next grade or graduate even if they haven’t mastered the course material. Grade inflation is also endemic at the college level. Teachers there compete for good student ratings by offering easy courses and high grades. At colleges of lower academic standing this practice is also encouraged by administrators so that tuition fees aren’t lost by students dropping out. And at elite colleges once known for high standards, core requirements have been dropped in favor of the cafeteria curriculum — a menu of popular, less demanding elective courses. Competition between colleges has shifted from academics to fringe benefits — cafes in libraries, climbing walls, gourmet dining halls, and fun and frolicsome junior years abroad.

Monopolistic models are not the US way

Educational monopolies stifle competition and create major civil discord, e.g., over the teaching of the Bible, prayer, sex education, alternate life styles, environmental instruction, etc. Public school monopolies are prone to fads touted by unions and teachers colleges and fail to address differences in student capabilities, styles, and motivation. They stifle innovative teachers and hinder students from moving ahead at their own speed. Common Core is a classic example of a centralized, anti-innovation, monopoly model, one that had a destructive effect in Massachusetts by overthrowing what was then the best public school curriculum in the nation. The other flaw in Common Core is its limitation to a pure skills approach. Curricular content is no less important than abstract skills. Indeed, no sane pedagogy would try to teach skills except as embedded in well-motivated, essential curricular content.

Right now public education at the state and big-city level is dominated by the iron triangle of state and urban “educrat” bureaucracies, teachers unions, and ed schools. State and municipal licensing is used to keep qualified professionals out of the profession so that they don’t compete with tenured union teachers. The motivation of such licensing is protectionism — for the state educrats, for the unions and their members, and for teachers colleges. Mentor / apprenticeship programs for starting teachers should be encouraged as a practice more conducive to fostering good teaching than cumbersome state licensing procedures.

Teachers are aggrieved parties in this system as well. The talented ones are paid the same as the mediocre ones and forced to teach mediocre curricular materials. Their pensions and health insurance aren’t fully portable as they should be. Portability is as important to teachers as it is to children — so that they can sort themselves into the schools that best match their own interests and talents. School chairmen and principals should similarly have the freedom to hire the teachers they want and set their own tenure, hiring, firing, promotion, and salary standards, as specified in a written employment contract. Those administrators who abuse this freedom will either be sacked by their school board, or the school itself will close when parents take their vouchers and children elsewhere.

With decentralization and competition in K-12 education, innovation will become more common and the successful innovations adopted quickly and widely, such as:

- distance learning,

- integration of classroom work with apprenticeships,

- vocational schools,

- ability grouping (tracking) in consultation with parents,

- the awarding of professional certificates instead of diplomas,

- adult learning,

- mid-morning start-of-school-day for teenagers, etc.

Four-year colleges

College costs and student debts pile up during four years of marking time that could have been spent earning money or mastering a profession

Finally, reform shouldn’t just be confined to elementary and secondary school education. Present four-year colleges are a waste of time and money for many attendees and a growing burden on students, parents, taxpayers, and the economy. Colleges should no longer be four-year post-puberty playpens but instead professional schools. That means that a rigorous liberal education should be completed by the end of 12th grade. Impossible? Not at all once one realizes that US elementary and middle schools are largely a waste of time from an educational standpoint. Supply real learning during these years and high schools will then be able to accomplish what the colleges profess to be about but are clearly failing to accomplish.

The 10% or so of high school graduates who actually need, and can benefit, from a traditional three or four year college program — whether in the humanities or sciences — should be expected to have mastered, as a prerequisite to high school graduation, solid, advanced placement level courses in calculus, statistics, and a major foreign language. (A recent Wall St. Journal op ed claimed that calculus isn’t necessary for high school students, just statistics — ignorant that a solid foundation in statistics requires the calculus.)

Public colleges should admit purely on the basis of merit. Private colleges should be allowed to manage their own admissions policies. But praise is due to the California Institute of Technology which, though private, has admissions policies that are largely merit based, in contrast to the many colleges that are surreptitiously also using racial criteria. To facilitate this maneuver, some have even been dropping admissions tests such as the ACT and College Boards as well as writing tests.

The one exception to the mandatory exit of the federal government from education should be scholarship support for student majors in the sciences, math, engineering, and critical foreign area studies. These scholarships, being a national defense imperative, would come out of the Defense Department budget. The unconstitutional Education Department would no longer be necessary.

We anticipate that as colleges change from post-secondary playpens to professional schools, most students will become focused on academic accomplishment rather than protesting in the streets and harassing non-conforming students and teachers through speech codes. And with the ongoing collapse in humanities enrollment, colleges may be encouraged to lay off or retire without replacement their post-modernist professors and create small, lean humanities departments with genuine scholars rather than ideologues.

Click here to go to the previous Founders Broadsheet (“Florida takes jackpot for amendments on November ballot”)

Leave a Reply