by Richard Schulman

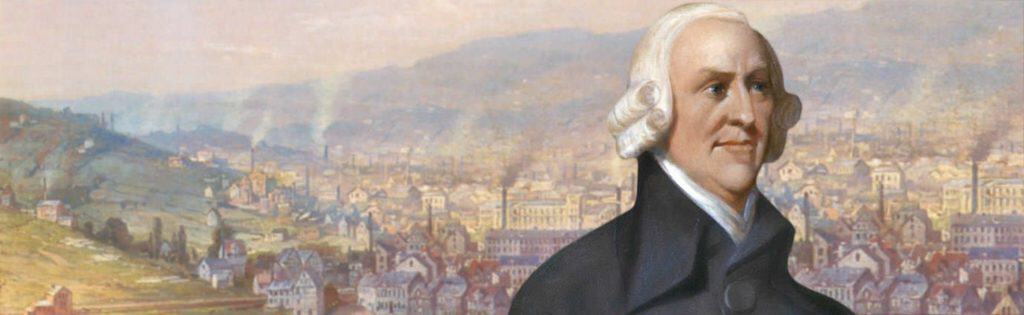

Spencer P. Morrison, a frequent contributor to American Greatness, is against free markets, free trade, and the idea that the division of labor has anything to do with improvements in standards of living. Contrary to Adam Smith, Morrison writes, it’s not the division of labor that makes things cheaper. Rather “technology drives long-run economic growth, not labor specialization.” Morrison seeks to bolster his argument with overheated language:

[M]any economists are crooks and liars. The biggest lie they tell us is that international free trade makes stuff cheaper. It doesn’t. It simply enriches the white-collar gangsters who run our banks—the very people who so often fund “libertarian” think tanks.

Any shopper at Walmart or a well-stocked produce market knows that free trade does make stuff cheaper. While technological innovation is indeed a major driver of long-run economic growth, only a stubborn protectionist would have thought it necessary to make that point by belittling Smith’s groundbreaking discussion of the division of labor and David Ricardo’s comparably famous discussion of comparative advantage in trade. Both of these are essential enablers of new technology introduction.

Technological innovation requires an already extensive division of labor for a cohort of inventors and engineers to even exist. It requires the scale provided by a mass market — enlarged by free trade — to make innovations profitable and spread their benefits globally. Entrepreneurs, their employees, transportation industry, banks, energy companies — these are all required to finance, mass produce and distribute technological innovation. Schools, publishing houses, and libraries are needed to preserve knowledge of the science and technology newly won and to reproduce the next generation of inventors, engineers, and collaborators.

Many of the inventions that drove the industrial revolution couldn’t have even taken place without the antecedent specialization that made it possible to mechanize individual functions one by one. The same is the case today with robots. Economist Ludwig von Mises made this point before the robot era in his magnum opus, Human Action:

The division of labor splits the various processes of production into minute tasks, many of which can be performed by mechanical devices. It is this fact that made the use of machinery possible and brought about the amazing improvements in technical methods of production. Mechanization is the fruit of the division of labor, its most beneficial achievement, not its motive and fountain spring. Power-driven specialized machinery could be employed only in a social environment under the division of labor. Every step forward on the road toward the use of more specialized, more refined, and more productive machines requires a further specialization of tasks.

One can demonstrate the error in Morrison’s celebration of technology at the expense of the division of labor by considering how little technology would get invented and developed if ten IBM scientists were stranded on a desert island with no connection to the rest of the world. The scientists would be forced to spend all their time just foraging and making clothing and shelter for themselves. Leonard Read’s famous essay “I, Pencil” shows how the knowledge and materials to produce so simple an object as a lead pencil requires a division of labor and distribution of knowledge involving millions of people.

Morrison’s attack on Ricardo’s theorem of comparative advantage in trade is equally ill-advised. Ricardo’s theorem is an extension of Smith’s emphasis on the centrality of the division of labor. If left unimpeded, markets tends to organize themselves so that even low-productivity producers find a useful role by producing what they are most productive at and trading with advanced producers for the complementary products in which the latter excel.

Free markets and free trade provide the competition that spurs technological innovation and spreads it quickly over the planet. Without an extended division of labor to provide the labor and intermediate goods needed to produce the new technologies, inventions die aborning, as does long-term growth. Only rigorously curated national security considerations should be allowed to stand in the way of this imperative.

Protectionist arguments have been around for four centuries, but it can’t be said that they’ve improved with age. Trusting hope over reason, an uncritically pro-Trump press can’t resist hosting journalists to flog this dead horse. Mr. Morrison’s attack on one of the greatest achievements of the Enlightenment — Adam Smith’s anchoring of classical economics in the division of labor — is something of a new low. By hosting such stuff, the otherwise admirable American Greatness isn’t so great.

Leave a Reply