by Richard Schulman

There’s a consensus among the few scholars who have investigated the subject — Daniel Bell, Jacques Barzun, and Charles Murray — that the last golden age of the arts ended by the close of the 19th century. Many artists also agreed, reveling so much in that recognition that they called themselves the Decadents. Distinguished works of art have certainly been produced subsequently but in ever reduced quantity and quality. Why the decline happened and how it might be reversed is our present concern. But first — what ages are we to take as standards?

Greece

The first golden age of the arts was in Greece during the 8th through 4th centuries BC. The arts flourished in a society that founded new sciences, mathematics, and history; that expanded throughout the Mediterranean world and beyond and that defeated a mighty Asiatic empire far more wealthy and populous than itself. It produced the two Homeric poems; the Athenian theater of Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, and Aristophanes; the sculptures of Phidias and the Parthenon frieze, Myron, Praxiteles, Polykleitos, and the Artemesion bronze; the lyric poetry of Archilochus, Sappho, and others (almost all now lost); the architecture of the Acropolis and temples throughout the Mediterranean world; the histories of Herodotus and Thucydides; and the philosophies of the pre-Socratics, Plato, and Aristotle.

China and India

India’s golden age of poetry, drama, science, and the arts occurred in the 4th through 6th centuries AD during the Gupta empire. China’s was during the Tang (poetry, painting) and Northern Sung (poetry, painting, science) — the 7th and 8th and 10th to 12th centuries AD, respectively.

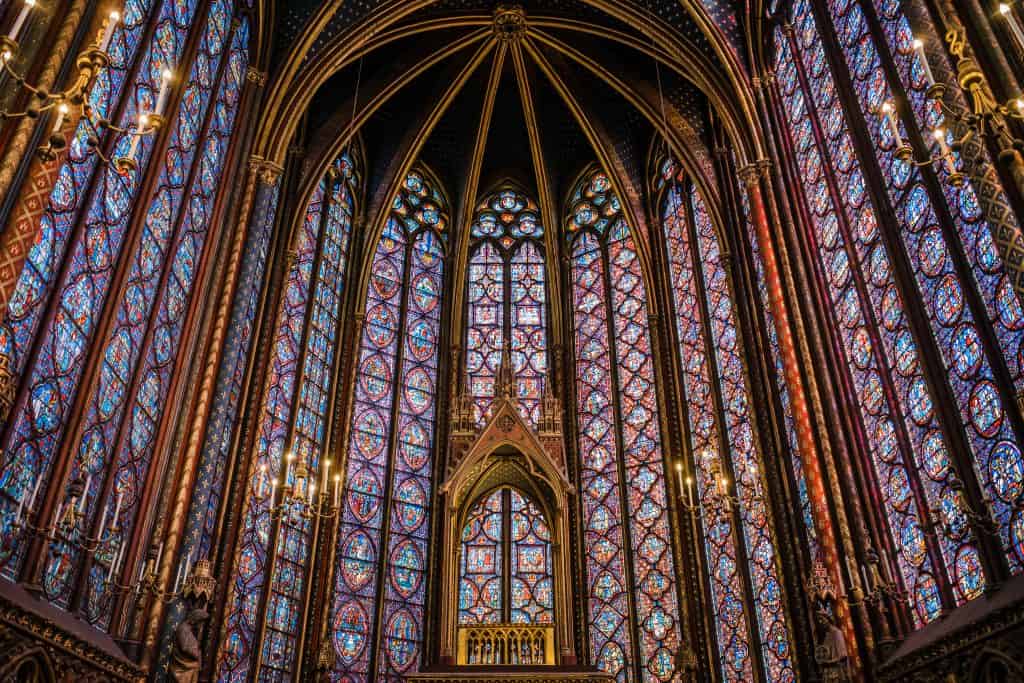

Middle Ages

With the defeat of invaders from the north and east and the revival of commerce between Europe and the Mediterranean world, Europe enjoyed from the 12 through 14th centuries its medieval golden age of troubadour lyrics and poetic epics, including Dante’s; sagas in prose; Giotto’s frescos, and the neo-Platonic-inspired architecture of the Gothic cathedrals.

Renaissance and Baroque

The 15th through 17th centuries in Europe featured a golden age of the arts concomitant with global exploration and the revival of study of the Greek and Latin classics. It was an age of countless masterpieces in painting and architecture in Italy, Spain, Flanders, Germany, and the Netherlands. This continued in the 16th and 17th centuries amidst the scientific and mathematical discoveries of Copernicus, Kepler, Galileo, Harvey, Newton, Descartes, and Leibniz; in theater, Marlowe, Shakespeare, Lope de Vega, Calderon de la Barca, and, in the prosperous Dutch Republic, Vondel; in prose, Cervantes and Rabelais; and in poetry, France’s Villon, sea-faring Portugal’s Camões, and England’s Spenser, Donne, Milton, and Marvel.

Classical and Romantic periods

The last great golden age of the arts in Europe spanned the 18th century into the second half of the 19th. In music, it included Handel, Bach, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, and Brahms. In opera, besides Handel and Mozart, it included Rossini, Donizetti, and Verdi; in ballet, the French and Russian schools. In poetry and theater, it included Goethe, Schiller, and Pushkin; in lyric poetry, Wordsworth, Shelley, Keats, Tennyson, and Heine; in novels, Manzoni, Stendhal, Balzac, Flaubert, Zola, Dostoevsky, Turgenev, Tolstoy, Austen, Thackeray, George Eliot, Trollope, and Thomas Hardy; and Victor Hugo in all three genres. Among the great painters were Goya, Constable, Gainsborough, Turner, Corot, Manet, Courbet, the Impressionists, and van Gogh.

Why is there no contemporary golden age of the arts?

There are many fine works of art in the 20th century, but in diminished quantity: some music by Stravinsky, Saint-Saëns, and Prokofiev; Balanchine’s ballets; the New York City paintings of the “Ashcan School”; some Frank Lloyd Wright buildings; Willa Cather’s novels; some poems by Rilke, T.S. Eliot, and Yeats, and some Russian poems that managed to escape Stalin’s bullets or gulags. (Cinema’s history is too brief to talk yet about golden ages vs. stagnant periods.)

The reader can doubtless name a few others but would be challenged, we believe, to credibly argue that the contemporary period has been so rich in masterworks as to be called a golden age.

Daniel Bell’s Cultural Contradictions

We are not alone in this judgment. Daniel Bell, in his widely cited The Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism (1976) argued that capitalism, by creating an abundance of wealth, created a hedonistic consumer culture that undermined the work ethic that founded capitalism. In his words, “When the Protestant ethic was sundered from bourgeois society, only the hedonism remained, and the capitalist system lost its transcendental ethic.”

Bell is right that the “transcendental ethic” — typically mediated through religion — has departed from much of the modern Western world and most of its artists. This has arguably damaged the quality of modern artistic output. But he’s wrong in his deterministic view that prosperity inevitably produces decline. The opposite is closer to the truth. The Greek, medieval, Renaissance, Baroque, and Classical-Romantic golden ages of the arts were all offshoots of rising prosperity and enhanced possibilities of individual development.

From Dawn to Decadence

Jacques Barzun’s From Dawn to Decadence…1500 to the Present (HarperCollins, 2000) has a more accurate view of the causes of relative decline of the arts in the modern period. He blames intellectual decay — the intelligentsia — for the decadence, pointing to the two great political disasters of the 20th century, Communism and Nazism:

The modern attempts at genocide were ignobly intellectual: the kulaks’ existence contradicted the theory of Communism, and [in accord with the new pseudo-science of eugenics] the German victims were ‘racially harmful’ to the nation.

The Russian scholar Gary Saul Morson casts further light on Barzun’s observation:

Anyone can succumb to ideology. All it takes is a sense of one’s own moral superiority for being on the right side; a theory that purports to explain everything; and—this is crucial—a principled refusal to see things from the point of view of one’s opponents or victims, lest one be tainted by their evil viewpoint.

The attack on literature

Rene Wellek’s 1982 book The attack on literature and other essays notes that the modern attack on the arts comes under multiple pretexts:

- that the arts are conservative and “rooted in social elitism…a weapon in the hands of those who rule,”

- that all art must be rejected that comes out of societies that had colonies, slaves, or relegated women to inferior roles,

- that writing is pointless because language is inadequate to express thought, and

- that there are no standards in art, just arbitrary subjective opinions.

Contrary to anti-art ideologues in university humanities departments, the arts invite us to consider the wide world in all its complexity and from differing standpoints from which we had hitherto viewed it. A golden age of the arts typically occurs in an age when (1) artists are deeply trained in their crafts, (2) create for audiences conversant with the best art of the past; and (3) both artists and audience are embedded in a culture sharing a sense of purpose in life and commitment to goals that transcend consuming, pleasure seeking, and dying in a purposeless universe.

Murray’s Human Accomplishment

This approaches the analysis presented by Charles Murray in his important 2003 book, Human Accomplishment: The Pursuit of Excellence in the Arts and Sciences, 800 B.C. to 1950. Murray believes that both science and the arts have been in decline since the early 20th century, and he makes an attempt at quantifying these perceptions in terms of scores based on frequency of citation. He sees peaks of human accomplishment — what we are calling golden ages — in most of the same times and places we do. He attributes the falling off to a decline in the belief

that life has a purpose and that the function of life is to fulfill that purpose….Purpose and autonomy are intertwined with the defining cultural characteristic of European civilization, individualism….Aquinas made the case, eventually adopted by the Church, that human intelligence is a gift from God, and that to apply human intelligence to understanding the world is not an affront to God but is pleasing to him….Faith and reason are not in opposition, but complementary….Only a few eras in human history have had the fortune to possess the resources of both rich, vital structures and transcendental goods at the same time — the eras that we look back upon as golden ages.

Art and religion

Murray is convinced that “religion is indispensable in igniting great accomplishment in the arts.” But “Today’s creative elites are not just overwhelmingly secular but often hostile to the idea that transcendental goods have any meaning.”

The religious belief need not necessarily be that of a traditional religion. But it can’t be an anti-human ideology that views humans as a blight on the planet, hopes for fewer of them, and wants a government that will make them consume less.

The decline of the elite

Elites used to sponsor and generously fund the “high” arts — ballet, opera, symphonies, and chamber music concerts. Increasingly, elites are more likely to be found at rock or grunge concerts and similar venues. Walt Disney no longer popularizes classical music, as it did once with “Fantasia.” As a reviewer in the Times Literary Supplement wondered:

[W]hy do American elites no longer identify as culturally elitist? For a long time…the fine gradations separating high or academic art from ‘commercial’ or otherwise stigmatized forms lined up with certain social stratifications. Fancy people enjoyed fancy things, like opera and ballet, or at least they pretended to enjoy them to keep up appearances. But the glue that stuck ‘highbrow’ and ‘lowbrow’ culture to their equivalent class positions has flaked away…[E]lites in the US no longer identify with the traditionally ‘highbrow’ arts…Instead, everybody enjoys everything according to personal taste.

Josephine Livingstone, “Art and part,” TLS, March 27, 2020.

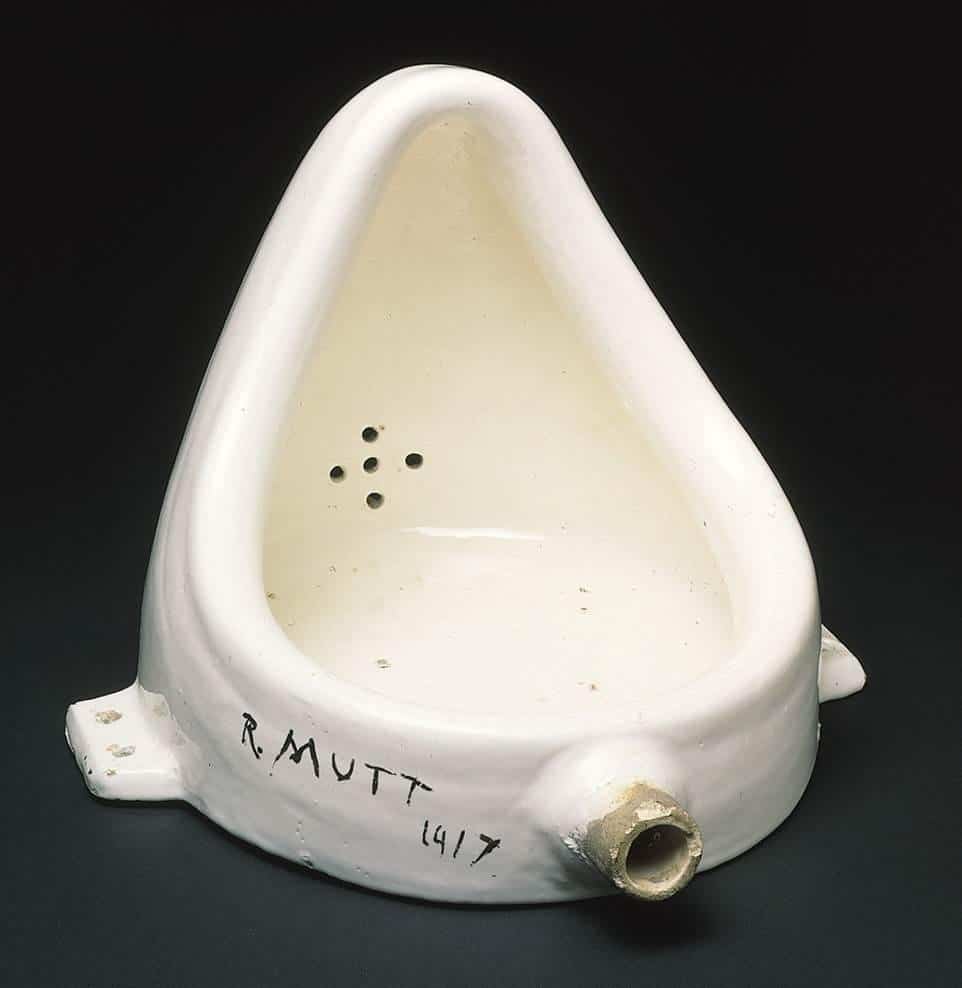

Corrupted artists

As the late pop artist Andy Warhol put it, “Art is what you can get away with.” With such debased standards of art and purpose, why should any art student train himself in long years of drawing, color studies, art history, and apprenticeship as the great Renaissance painters did?

Our music schools are producing many fine musicians but few composers capable of writing a piece of classical music worth more than two minutes of listening. Hell is being forced to endure a concert-length performance of Stockhausen, Milton Babbitt, John Adams (no relation to the original), or Steve Reich.

In the face of a dearth of contemporary music that audiences can stand, classical music organizations have concentrated their programming on the great classics of previous centuries.

Visitors to art museums experience a similar response to the latest products on display there. After spending great amounts of time viewing the paintings from the Renaissance up to the early 20th century, visitors who wander inadvertently into rooms featuring the art of the past few decades — splashings on walls, strange sounds emitted by boxes, piles of wood, metal, and styrofoam strewn on the floor — make an embarrassed dash for the nearest exit, as though they had stumbled into a dressing room for the opposite sex.

What hope for a new golden age of the arts?

Shelley thought that “Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world” while W.H. Auden, reflecting a later demoralization, asserted that “Poetry makes nothing happen.” We now know the circumstances in which a golden age of the arts becomes possible and new Shelleys can thrive. Given that all of us will flourish in such a world, not just the artists, the re-creation of such an integrated world of scientific, economic, and artistic flourishing is a goal worth keeping in mind for perspective regarding the daily squabbles of political life.

You ought to be a part of a contest for one off

the best blogs on the web. I wiull recommend this web site!

My site :: Manuela